It

came as something as a surprise to me then, that a few years ago, I found

myself seeking out sources of folk music for a project I was working on. I had

started a site-specific choreographic collaboration centred on the notion of

The River in urban life, and was interested in the way in which this was

expressed in music. I found myself looking at a book of English folk songs in

an idle moment, wondering if waterways were much in evidence. “Gently flows the

winding river” went the first line of one, and later continued “...I live not

where I love”, a poignant sentiment for me at the time, as I was in an

exquisitely difficult and doomed long-distance relationship. I decided to make

my own version of the song as a part of the project, although it rapidly

evolved into something more personal, and private. Although not without its

flaws, I felt oddly, that in some way I had uncovered a magic spell; of release

or of earthing. You can hear the result here:

Some

time later I quit the collaboration, but turned back to the books of folk music

at the library, feeling that there was still something unfinished there for me.

In amongst all the ballads and jolly military tales that left me cold I

discovered a narrow but very rich seam of material I’d had no idea was there: unforgettable

songs of love and heartbreak. Folk material has a fantastic, unselfconsciously

direct way of expressing certain kinds of experience: a breakup is not just a

loss for instance, but often an actual death.

Sometimes in art there is a magical combination, when great abstract reasoning

meets a beautiful physical surface, and I found hints and sparks of this in some

folk songs that had been arranged by classical composers; particularly by that group

of men who were actively transcribing, arranging and publishing folk songs at

the beginning of the twentieth century: Cecil Sharp, Ralph Vaughan Williams,

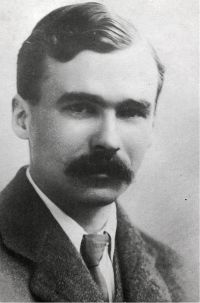

Gustav Holst. And George Butterworth.

It’s a controversial matter these days, as to the validity, or honesty of the motivations of that group of collectors and arrangers, but from a very personal point of view, there is a piquancy for me in the straitlaced bourgeois gentleman unearthing some inner authenticity through his apprehension of this culture that is both Self in its englishness and Other in its historical provenance and class; absorbing and changing it, and at the same time being irreversibly changed by it. Of course, I may well be describing myself in some ways here too. We can still witness this curious combination not just through Butterworth’s music but through surviving film footage of he and Cecil Sharp Morris dancing: their Edwardian stiffness is animated by an idea of pastoral physicality and ease. The dance they are acting out is drawing out something from them, as surely as they are using it to express their own notions of a prelapsarian idyll. It’s hard to be sure because the footage is so grainy, but there is a moment when Sharp and Butterworth crash into each other. They really seem to be laughing, having a real hoot.

It’s a controversial matter these days, as to the validity, or honesty of the motivations of that group of collectors and arrangers, but from a very personal point of view, there is a piquancy for me in the straitlaced bourgeois gentleman unearthing some inner authenticity through his apprehension of this culture that is both Self in its englishness and Other in its historical provenance and class; absorbing and changing it, and at the same time being irreversibly changed by it. Of course, I may well be describing myself in some ways here too. We can still witness this curious combination not just through Butterworth’s music but through surviving film footage of he and Cecil Sharp Morris dancing: their Edwardian stiffness is animated by an idea of pastoral physicality and ease. The dance they are acting out is drawing out something from them, as surely as they are using it to express their own notions of a prelapsarian idyll. It’s hard to be sure because the footage is so grainy, but there is a moment when Sharp and Butterworth crash into each other. They really seem to be laughing, having a real hoot.

A Blacksmith

Born in 1885, Butterworth was the son of a wealthy industrialist whose successful Edwardian musical career, begun at Eton College, was abruptly ended when he joined up and became an officer in the trenches of the First World War. He died from a sniper’s bullet in the Battle of the Somme in 1916. He actively recorded folk songs from the working class inhabitants of rural Sussex, arranging some of them for voice and piano, and many of his compositions were built on a foundation of folk material.

I first came across Butterworth in his arrangement of ‘A blacksmith courted me’, a song collected by Vaughan Williams in 1909. The protagonist in this song is a world apart from the dreary maids and lads in the songs I remembered from my youth. ‘A blacksmith’ projects a powerful sense of desire and longing overwhelmed by anxiety and loss. This desire is for a man, the blacksmith, with “his hammer all in his hand”, and Butterworth’s arrangement, in its simple cadences and subtly ambivalent harmony, brings out the complex allure of that unattainable object; perhaps the transgressive desire of one man for another, or of the aristocrat longing for the assumed simplicity or honesty of the proletariat, we can’t know for sure. The blacksmith is objectified as an impermanent thing of beauty, through his physical attributes – “he looks so brave and clever” – which establishes a complex position for the protagonist of passive watching and imagining as if from a distance. This creates a dissonance between the real blacksmith and his fantasy counterpart which is resolved in the bewildered, piercing repetition: “Strange news is come from abroad, strange news is carried, strange news is come to tell that my love is married” underlining the potency and agony of that unfulfilled desire, and the curse of that passivity.

I didn’t really know anything about Butterworth at this point. In some ways I still don’t, though I have read much about him. I don’t know if he desired other men, or where in his heart he felt that ache of longing for the unobtainable that the song pulled out of him. Wikipedia says that “the parallel is regularly made between the…subject matter of A Shropshire Lad (a song cycle of his on texts by A E Housman)…and Butterworth's subsequent death during the Great War”. It’s easy to romantically associate this unfulfilled longing in the folk song arrangements with Butterworth’s future fate, too. His life and work as a composer are in some ways as tantalisingly gone from us as the blacksmith is.

Butterworth arranged these songs for piano and voice, and his discourse is a solidly public, art-song one. My music is concerned in some ways with a kind of interiority: work that demands a psychologically private medium that headphones and domestic speakers provide. So when I embarked on my own version of Butterworth’s ‘A blacksmith’ I decided to use the computer and my home studio to do it, rather than to write it down for public performance. It became a very personal project for me, and so, despite my own limitations – and learning as I went – I decided to sing it myself, too, in the same way those singers that Butterworth encountered on his collecting trips would have done. If Butterworth legitimises his folk material through the mask of the public performers, I wear Butterworth’s hand as a kind of glove, through which the folk material becomes manipulable. But also, because I play all the instruments myself (voice, piano and soprano saxophone predominantly), I act as a mouthpiece for the unnamed original songsmith and for Butterworth too. There’s many layers to this cultural costume: perhaps Oscar Wilde was right when he said "Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth."

My version falls into four sections, the three verses of Butterworth’s arrangement, with an instrumental interlude. I tried to make explicit those things that are implicit in the original: the heedless, denying simplicity of the opening, the slowly overwhelming anxiety of the second verse, and the emotional horror of the last, with its paralysis of shock and final, furious, self-defeating declaration. The music I wrote draws strongly on the very first phrase of Butterworth’s piano accompaniment, that twice-rising tone that then falls and rises again, curling around itself, never quite resolving harmonically.

The saxophone interlude refers to a specific, personal loss. It is a quotation of sorts, of a piece I wrote in the nineties for a friend who died shortly after. In fact I play this music on the saxophone that belonged to him. There’s a concatenation of longing in this brief song, then: for that doomed long-distance relationship I had just then lost, for the friend I had lost almost 20 years ago, and for the idea of writing classical music itself, in some ways. And too, the poignancy of Butterworth’s life and death, of his longing for something unreachable that spilled over into his arrangement, and that long lost original author whose blacksmith left them for that field in the sun.

A True Lover’s Farewell

After ‘A blacksmith’, I decided to seek out some more of Butterworth’s folk arrangements. I was a little surprised to discover that ‘A blacksmith courted me’ isn’t exactly typical of them. Most of them fall into the jolly romp category, though they share the deceptive simplicity of their arrangements. ‘A true lover’s farewell’, of all the arrangements in his collection, is perhaps the most doleful. It’s ambivalent though: the words are in some ways a passionate declaration of love and fidelity and yet the arrangement hints at something darker. When I played a couple of friends the recording by Roderick Williams and Iain Burnside, their first reaction was to laugh. I suppose this was because of the stark grandness of Butterworth’s gesture combined with the sweetness of the tune, I don’t know. He does seem to protest a little too much it’s true. But it seemed to me that Butterworth turns this sweet little song on its head: the accompaniment is overweening for a reason. It transforms the singer’s intent from a declaration of love into a honeyed lie. The lover is not true, there will be no return.

The core musical appeal of this song for me was twofold: the beautiful melody and the harmony. The tune is one of the catchiest I’ve ever worked with. It compels you to sing it. The harmony’s attractions are more complex: it is basically modal but hovers just on that border between major and minor, first shifting one way then the other. Butterworth cleverly works with the implied harmony of the tune to provide a wavelike alternation of tension and release, most notably on the last word of the first accompanied verse’s “Oh fare you well for a while”.

In general, folk songs fall very much into a strophic form, and Butterworth mostly follows this – as he does in ‘A blacksmith’ – by writing an accompaniment that repeats for each verse. His arrangement of ‘A true lover’s farewell’ doesn’t do this: it is through-written, each verse accompanied differently, though the harmonic underpinnings remain the same. It builds from literally nothing – he leaves the first verse unaccompanied – to a deep, sonorous, baleful climax at the end of the third. The scrap of melody the piano provides as a brief introduction sets the tone: low in register, in stark octaves and rooted in the minor-key aspect of the tune’s double nature. The accompaniment acts as a kind of shadow to the voice, undermining the guileless veracity of the text’s declarations. The bigger the singer’s claims become, the more thundering the denial has to be.

One of the main things about my version is that everything in it is in some ways false. The voice is electronically manipulated in different ways, the piano is an electric one; in fact there are no acoustic instruments in it at all. The instrumental part I added after the third verse is made up of a web of distorted transcriptions of birdsong, a kind of alienated robotic dawn chorus. Despite what the singer – me again, wearing a three-sided digital mask this time – asserts, the plastic fakeness of everything else about the song denies it. The unexpected but neat cadence of the end is like a little bow tied around that pat falsification, as if to say: believe THAT, sucker.

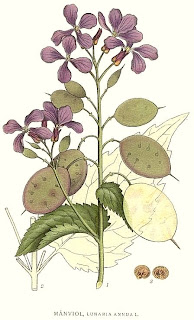

The cuckoo

The first thing that appealed to me about ‘The cuckoo’ is the way in which it talks about death. “The grave it will rot you and bring you to dust” is sung in the same chirpy tone that gives “The cuckoo is a merry bird, she sings as she flies” its jaunty appeal. In fact, the only thing that makes this song cohere at all – the text is all over the place – is the repetition of the melody and its accompaniment. Like an accomplished film actor barely moving their face, we are able to project a host of contrasting emotions and ideas onto the impassive unrolling of the piano part. It’s a very twentieth century setting in this regard.

Butterworth sets up a lovely bouncing rhythm that is very definitely in three, only to trip us up with a couple of bars that are three sets of two. Like ‘A true lover’s farewell’, the harmony fluctuates between the major and the minor, though it’s much more prominent in the tune here.

I changed the text quite a lot. The folk tradition has always had a very free approach to the malleability of language. You rarely find two versions of a song that are the same. I had changed some of the words in ‘A true lover’s farewell’, as I found I couldn’t bring myself to sing the oh-so-Victorian affectionate epithet “dear”, and went further in ‘The cuckoo’. I made it more generalised and gender neutral. The way the text is structured is like the links of a chain, the ideas join up to one another though they don’t really make a coherent whole. The interesting thing that got me thinking was the transitions: you don’t necessarily notice but you end up somewhere completely different from where you started. Butterworth irons out these differences, I chose to exaggerate them.

The beginning of my version is full of summer languor. It picks up speed and becomes more rhythmic when Death becomes the subject. I liked the idea that it’s mortality and the physicality of death that inspire the movement and energy that make up the dance-like section. Above all, the psychological landscape this song describes is rooted in physical Nature. So like I did in ‘A blacksmith’, I use found and environmental recorded sound to root my version in a twenty-first century setting: there’s bees and birdsong and the sound of aeroplanes overhead. The cuckoo is absent, but the saxophone alludes to it.

Keith Johnson, London, 2013.